Australia’s Business Investment Challenge

Introduction

Good evening ladies and gentlemen and my thanks to the Research School of Economics for inviting me to give this address.

Sir Leslie Melville’s legacy is still evident today – during his time at the Commonwealth Bank he set up an economics department that provided the foundation for the research arm of the Reserve Bank.

Indeed, I understand that he was a strong candidate to be the first Governor of the RBA.

As Chairman of the Tariff Board, he took a principled stand in defence of an important public institution that lives on today in its modern form as the Productivity Commission.

Sir Leslie was from all accounts very talented but also pragmatic and principled.

When called upon, he stepped up to assist successive governments in meeting the challenges they faced – be it Australia’s entry to World War II, the setting of tariffs or the distribution of grants to the states and territories.

As the saying goes, the more things change the more they stay the same – and my now 25 years in Treasury attest to that.

I am speaking tonight at an important point in Australia’s economic transition as we move beyond the end of the mining investment boom – and it is timely to reflect on the state of the economy, where we might be headed and what may be needed.

Last week, we released a report on the issue of business investment prepared for the meeting of Commonwealth and State Treasurers held on Friday in Sydney.

This work was commissioned late last year because we wanted to understand why business investment in the non-mining sectors of the economy was not picking up as our understanding of the business cycle suggested it should.

This phenomenon was shared by many other countries.

Pleasingly, what we found affirms our view that we have not un-invented the business cycle.

But we are in a very long cycle and we underestimated how deep the scars of the global financial crisis run in the minds of business owners and managers.

We gained a range of other insights from the exercise that I will discuss later but it reinforced the need for economic policy advisers, like the Treasury, to understand better what is actually going on in the economy and the extent to which our national economic story varies across states and regions and between sectors of the economy.

This project also reflects a broader focus at Treasury on engaging more widely and deeply with stakeholders – and, to this end, we have now established significant offices in Sydney, Melbourne and most recently in Perth.

We are also visiting regional areas to ensure we are connected with economic change outside of the major capitals.

I personally have travelled to Horsham, Townsville and Orange while others on my Executive have led trips to Ballarat, Melton and the Northern Territory.

Next week our Executive Committee will travel to Perth and some of us will visit Kalgoorlie as part of that trip.

We are also increasing the diversity of people we bring in to Treasury including hiring far more from the private sector and from professions other than pure economics and law to broaden the experiences we can draw on in our analysis and forecasting.

Now, economic forecasting generally is an unenviable task – because you will almost certainly be wrong – and picking turning points (be they on the up or downside) is not something on which anyone has a great record.

The GFC was a brutal reminder of economists’ and the finance sectors’ frailties in this regard. All economists should be humble!

However, in the second half of last year, we started to feel that things might be about to take a turn for the better, both domestically and globally.

So we are pleased that this is starting to come through in the economic data.

Of course, I am the first to admit that there are still risks to this more positive outlook particularly when we consider how geostrategic and financial risks in our region might play out.

Business Investment

One thing we know will be vital to our economic prosperity going forward is business investment.

Investment in new productive capacity creates employment opportunities, raises future incomes and supports innovation.

Recent Treasury research indicates that Australia has generally been more reliant on capital deepening than multifactor productivity growth to fuel its aggregate labour productivity growth.

This research is publicly available on the Treasury Research Institute website.

We are doing far more research in Treasury but some necessarily must remain confidential.

Productivity-enhancing policies are vital because of the link between productivity gains and real wage increases.

We know that higher productivity is the best way to increase real wages across the economy and, based on Treasury’s recent analysis of longitudinal business data, it is clear that average real wages are higher for businesses with higher labour productivity.

Both capital deepening and multifactor productivity will be important to support further growth in labour productivity – so business investment is critical to our economic prosperity.

Recent trends

Over the past decade, Australia’s experience with business investment has played out in two starkly different stages.

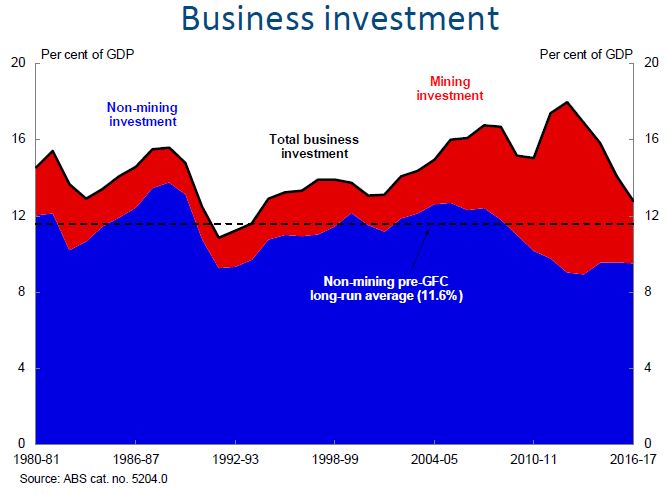

Chart 1 – This chart shows the unprecedented investment boom to build new supply capacity in the mining sector in response to strong demand for resources and higher commodity prices.

Such was the strength of the mining boom that total business investment increased as a per cent of GDP noticeably over this period.

This was one important factor in our economy’s resilience through the GFC, supporting jobs in a whole range of industries and seeing benefits flow on to wages and capital returns throughout the economy.

Of course, it is hard to know precisely why our economy fared so well during the GFC.

The flexibility of the economy, prudent monetary policy and a sound financial system – as well as demand from China – all played their part but it is difficult to single out any individual factor.

While mining investment declined for a time during the GFC, the demand for our resources was such that mining investment increased through to its peak in 2012-13, helping to counteract the global tide of recession through that period.

Since then, mining investment has rapidly receded.

Crucially, business investment outside of the mining sector did not take up the slack as the trend in mining investment reversed.

The share of non-mining business investment as a per cent of GDP began to fall following the GFC, and in recent years has fallen to around its lowest share of GDP in the past 50 years.

In 2016‑17, non-mining business investment was around 9 per cent of GDP.

As is clear from the chart, this is between 2 and 2 ½ percentage points of GDP below the long run average prior to the GFC – so there remains a gap that we would hope non-mining investment could fill.

In an environment of low interest rates and generally positive economic developments the extent of the weakness in non-mining investment was somewhat perplexing.

Australia has not been alone in facing this challenge.

In meetings with my counterparts from the New Zealand, Canada, UK and Ireland Treasuries over recent years weak business investment has been one of the key concerns discussed.

The Business Investment Review

At the December 2016 meeting of the Council on Federal Financial Relations, Treasurers collectively asked Heads of Treasuries to conduct a review to understand what was happening in more detail.

The Heads of Treasuries group provides an important avenue for myself and my counterparts to exchange information about the economy’s performance in different sectors and regions.

This kind of consultation is essential to make sure we have a clear picture of what is happening throughout the economy.

Whether running an asset management firm or the Treasury, I have always felt the need to have as broad a set of information points and views as possible.

We cannot just rely on data – historical or prospective – we need to know and monitor players in the real world and financial markets.

I learnt this first hand while I was posted with Treasury to the United States during the stock market crash of 1987.

The day after Black Monday, I visited New York where financial market traders and business people alike painted a dire picture of the economy.

The following day in Chicago told a completely different story with businesses operating far more in the ‘real’ economy much less concerned about those events – and they proved correct.

The lesson is to gather information from a wide range of sources and, in particular, not be too focussed on financial markets alone.

This was quite a different event to the deeper and broader financial crisis of 2008 where we saw the plunge in the financial markets drive contraction worldwide in the real economy.

So in order to understand why Australian business weren’t investing more we decided to ask the people who are at the coalface and making these decisions.

Over several months this year, the project team met with over 50 business leaders including the CEOs and CFOs of the top ASX‑listed companies and the Chief Executives of peak industry bodies while Kate Carnell led consultation with SMEs.

The project was led by the new Structural Reform Group that we re-established earlier this year to bring more focus in Treasury onto some of the biggest economic challenges facing Australia.

We were also able to use the offices that we have established in Sydney, Perth and Melbourne along with the Treasury departments in each of the States and Territories.

I held roundtables with key business and industry leaders and the project took us to each of Australia’s capitals.

Key findings of the Review

So what did we learn?

That there is no single answer – there is a very broad range of factors contributing to decisions on investment.

For obvious reasons, the businesses we spoke to in the resources sector indicated that their major investment decisions have been driven far more by headline factors such as falling commodity prices, as opposed to factors that are driven by government policy.

Other business leaders spoke about the impacts of technological disruption, which is happening at a rapid pace – transforming industries and the competitive landscape.

For some existing businesses, this is encouraging defensive business strategies while for others it creates opportunities.

And, of course, technological change is just one driver of the structural shifts in the economy that are impacting investment decisions.

These are a few examples which demonstrate that that growth is not broad-based, with variable sectoral outlooks for demand.

Regional factors are also very important.

And, of course, some of the businesses we spoke to were most concerned about the impacts of institutional settings and government policies.

The scars of the GFC

A clear message was the lasting impact of the Global Financial Crisis on attitudes to risk, as well as lingering uncertainty in the global economy.

In recent years, we have seen evidence globally and in Australia of more defensive business strategies such as increasing debt-to-equity ratios, dividend pay‑out ratios and share buybacks.

Dividend payments to shareholders have also been at historic highs and cash holdings substantial.

A persistent theme from contacts was a lower risk appetite from both corporate boards and investors.

There was almost universal feedback that uncertainty has been elevated for the past decade and that this is impacting firm behaviour.

As one executive said, the ‘scars’ of the GFC on business decision‑makers are deeper and more extensive than had originally been expected.

Many businesses discussed their increased use of downside scenario planning, relative to a decade ago, which appears to be adding a subjective risk premium to investment assessments.

Global uncertainty

If we think about the global economy over the decade, some of the reasons for this uncertainty are not difficult to spot.

The GFC was followed by a lingering sovereign debt crisis in Europe, while geopolitical tensions remain ever-present.

Markets have also had to understand and adjust to the unconventional monetary policy employed by some central banks in recent years.

All of this is to say that, while low interest rates and other factors have seemed to be supportive of business investment over recent years, a range of other factors have also generated uncertainty.

In this context, it is easier to understand businesses being more wary when making significant investment decisions.

Institutional and policy settings

Not all the uncertainty faced by business is the result of shifting global factors – some of it has its causes much closer to home.

All levels of government influence the business environment as they set the institutional and policy frameworks in which businesses operate.

Stable macroeconomic conditions, through credible monetary policy frameworks, responsible fiscal policy and sound financial sector regulatory environments remain central to long-term demand and growth in investment.

Businesses consulted were clear that, while much of the uncertainty is outside the control of Australian governments, the focus for governments should be on reducing uncertainty.

While non-profound – predictable, stable and transparent business regulation and supervision, at all levels of government, is an important precondition for business investment.

Energy

As has been well publicised in recent months, energy policy is a key example.

Bearing in mind that this was before the most recent policy announcements, in our consultations there was widespread concern around how energy policy uncertainty is contributing to investment uncertainty, higher power prices and poorer system reliability.

However, as policy advisors we have a critical role to play in ensuring that market structures incentivise the amount of capacity that customers actually value.

I don’t intend to join the chorus of commentary on energy policy beyond noting that I think it’s reasonably well accepted that the objective of any policy in this space needs to be the establishment of a credible and lasting mechanism that ensures the electricity sector can provide reliable and affordable energy for the nation while efficiently meeting its share of our international commitments.

Corporate tax

Many businesses were also very concerned that the firm commitment for company tax cuts has not yet become policy.

There is concern that Australia’s 30 per cent company tax rate imposes a large distortion on investment because it sets a higher rate of return hurdle for new investments in Australia than in other countries.

As I have said elsewhere, the starter’s gun has been fired with the UK, US and others all reducing or planning to reduce their rates of corporate tax.

Smaller businesses were also concerned that large multinational companies not paying their ‘fair share’ of tax put other businesses at a competitive disadvantage.

We will continue to work through the G20 and the OECD, to ensure that our tax laws provide a level playing field for Australian firms and the Government has also taken some unilateral steps through the introduction of the Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law and the Diverted Profits Tax.

If we are to remain competitive, there will inevitably be a need to lower corporate tax rates over time.

Of course the tax system needs to also provide the right incentives, increase efficiency and be sustainable.

Red-tape and regulation

Regulatory and red-tape burden was unsurprisingly another key feature of our discussions with businesses.

There is widespread concern about the red-tape cost of doing business in Australia and the impact of the regulatory environment on the investment environment.

Businesses feel that the cumulative burden of regulation on business is increasing, not decreasing, over time. They urged genuine efforts to ease this.

Monitoring and compliance costs for regulation significantly add to business costs. Companies said that they have had to spend significant amounts of money implementing new systems and procedures due to extensive regulatory change.

Many SMEs commented that they experience a disproportionately high regulatory burden as they do not have the same economies of scale that large companies do.

A recent Treasury paper – released through the Treasury Research Institute – outlined how small businesses experience the burden of regulation more keenly than larger businesses because they have fewer resources and are unable to take advantage of ‘economies of scale’ in order to understand, comply with and benefit from regulation.

I also know from my own experience how challenging this can be for small businesses.

Earlier this year my son took over a farm in Victoria.

The challenges he faces brought home to me just how expensive and difficult it is to deal with all of the tax and other such regulation at the Federal, State and local level.

This is real obstacle for many young and older people who want to take on a small business for the first time or start up their own venture.

I fear that policy makers in Canberra and in the States are not as alive to this issue as they should be when designing policy.

A lot of government regulation is justified but a question that we continually need to ask ourselves is have we got the balance right?

At the Council on Federal Financial Relations meeting last week, the Treasurers agreed that this will be an area of collective focus for Heads of Treasuries going forward.

Competition and innovation

Another policy issue raised in our consultation is the importance of getting competition policy settings right.

These should ensure that markets work in the long‑term interests of consumers, as well as encouraging innovation, entrepreneurship and the entry of new players.

Businesses who take up innovative and new technologies in order to be more productive should not be dissuaded by government policies which protect inefficient businesses.

By and large, it is very hard to think of any sector that would not benefit from more competition.

The reforms that followed the Hilmer Review in 1993 were instrumental to delivering more competition in the economy, which in turn has helped underpin economic growth in the decades since.

I have every expectation that the reforms following the Harper Review and, more recently, the work of the Productivity Commission will deliver the next wave of improvements in competition.

A significant package of legislative reforms that give effect to the recommendations of the Harper Review received Royal Assent on Friday last week and will come into effect shortly.

I would also like to thank Rod Sims and the ACCC for the very substantial contribution they have made to our competition framework and am delighted that they will play a pivotal role in the implementation of the changes going forward.

It has been terrific working with Rod and Peter Harris on these issues over recent years.

Regional transitions

Finally, structural and regional change was raised as a factor in business investment decisions.

As I have said before, in the 80s and 90s we delivered far reaching and robust economic reform which was supported by open debate in the bureaucracy and the community.

But, in the cosseted world of Canberra, we in Treasury did not always recognise the major social impacts of such structural shifts on the communities they affected.

I personally feel very sorry about this and have been cognisant of these challenges as we have approached more recent issues such as the sale of Arrium in South Australia.

Long-term unemployment and exit from the labour force by displaced workers are consequences that have serious economic and social costs.

We need to try to anticipate the likely effects of changes, such as the departure of a major employer, during policy development, and how to best manage them.

A recent Treasury paper – also published through the Treasury Research Institute – found that regional Australia has shown a capacity to adapt, innovate and reinvent to take advantage of new opportunities and recover from structural and cyclical challenges.

Education is a key factor – with high school education particularly important – as low skilled workers in declining industries are less able to take up jobs that require different skills.

The proximity to a larger centre is also a critical factor for particularly remote communities.

And the role of local leadership cannot be discounted – for instance, I met with the Mayor of Horsham in Victoria earlier this year and she is a terrific example of someone who can set out and promote a vision for the local area.

I also saw how these factors can come together when I was in Orange this year.

Orange has been challenged by declining employment in agriculture and manufacturing, but has reinvented itself with a strong tourism profile – based partly on its strength in wine making – which draws visitors and now residents from metropolitan areas.

While in Orange, I met a lovely couple, Angus and Sarah, who are small business owners that have built up a high-end leather goods business called Angus Barrett Saddlery.

A former stockman, Angus started manufacturing his saddlery and leather goods part time in 2000 – and has since built it up into a business that now employs 15 staff in its manufacturing premises and two stores.

With the benefit of the internet, their leather goods, which are all made in their workshop in Orange are sold Australia wide and internationally – and I can attest personally to their style and quality.

While there are other examples of regional towns that have that undergone similar transformations, not all places can reinvent themselves in this fashion or adapt easily in the face of significant structural change.

Some regions, particularly those which are geographically isolated and heavily reliant on a relatively small number of industries, will find it more difficult to adjust.

However, some regional centres in Victoria are seeing strong growth due to commuters moving further out, which has been facilitated by investment in regional rail and road upgrades as well as social infrastructure more generally.

A driver of this may be that housing in some capital cities is becoming more expensive.

The way forward on productivity

The lessons from all of this are difficult but important.

On the one hand, there may be little we can do to tackle some of these factors.

Governments cannot regulate the risk appetites of boardrooms, nor can Australia expect to significantly change the course of the global economy.

These challenges will take time to resolve and there is a degree to which we shall need to ‘wait-it-out’.

We can, of course, continue to be a voice for stable and measured economic and geopolitical policy, supporting the global rules-based order and remaining open to trade and investment.

But there are things we can do domestically.

There is a need for stable and consistent policy approaches to structural issues such as energy and taxation arrangements.

Much of this is in the hands of politicians and the past decade has certainly been one of extraordinary change and instability on that front.

But there is also a critical role for Treasury, the public service more broadly and public institutions, including universities such as the ANU, in ensuring the debate is well informed.

We have a responsibility to continue to provide clear and consistent advice about the policy reforms needed to support the economy over the longer term.

That is why we re-established the Structural Reform Group within Treasury.

I am pleased to announce that Dan Andrews, who is currently Deputy Head of the Structural Policy Analysis Division at the OECD, will also be joining Treasury early next year.

Among other things, Dan has looked in detail at the problem of encouraging productivity through structural reform and innovation – including the potential relationship between lower corporate tax rates and productivity – and we look forward to his contribution across our research work.

The productivity agenda

But if there is a lesson it's that we need to reboot productivity growth.

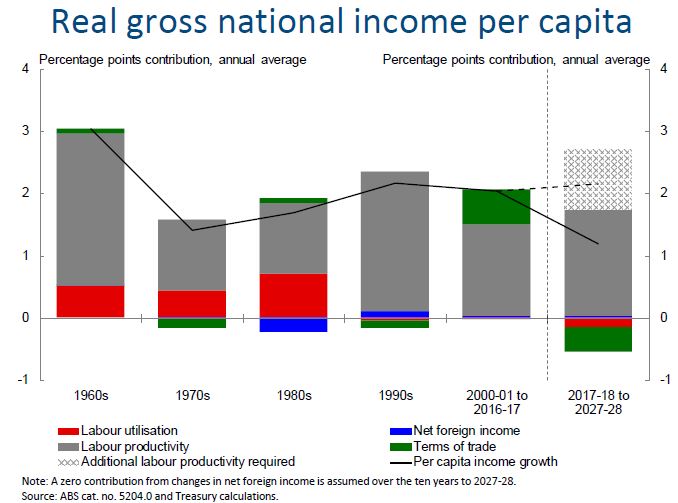

Chart 2 - As this chart shows, lifting our productivity performance will be key to sustaining the pace of income growth enjoyed over recent decades.

The Productivity Commission has set out a clear path forward across a range of these factors with its first 5 year productivity review released last week.

The report sets out a series of recommendations across the five areas it considers the most promising drivers of productivity growth – Healthier Australians, Future skills and work, Better functioning towns and cities, Improving the efficiency of markets, and More effective governments.

However, this report sets the challenge not only for Australian governments but also for the business and broader community because it makes clear that the long-term transformations that will set Australia up for the future will require trade-offs and prioritisation of objectives.

The first challenge is to be able to have mature debates about the policy settings, at all levels of government, that have the greatest potential to drive growth in the economy and ultimately improvements in living standards.

The health and education systems are crucial areas to focus on because these are central to the productive capacity of the population.

The need for increased productivity in the services sectors – which will attract more labour as they grow as a share of the economy – is also highlighted in the report.

As Treasury’s research shows, the movement of labour into and out of high-productivity sectors like mining and utilities sectors has muted cyclical effects on aggregate productivity – but it is productivity growth within the services sectors that is now key.

The Productivity Commission’s work is a comprehensive example of the kind of support that institutions can provide to governments to light the way on policy and reform.

The economic outlook

As I suggested earlier tonight, the good news is that since we commenced the Business Investment Review, we have seen a pick-up in business investment and healthy labour market conditions.

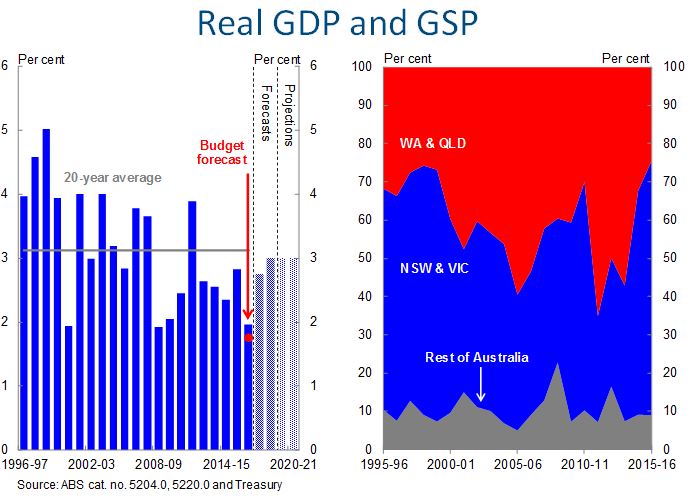

Australia’s economy as a whole expanded 2 per cent in 2016-17 – above the Budget forecast of 1¾ per cent.

This headline figure masks different outcomes across the States and Territories as would be expected given the different balance of industries across our nation.

At the most recent Heads of Treasuries meeting in September, we were encouraged by the fact that most of my State and Territory counterparts reported strong or improving economic conditions in their state.

Chart 3 – This chart shows that, during the peak of the boom, activity in the mining states accounted for over 50 per cent of total GDP growth – whereas more recently the large non-mining states have contributed the most to growth.

New business investment grew by 1.5 per cent over the year to the June quarter, the first positive through-the-year growth since the end of the mining investment boom.

Business investment grew by over 4 per cent in the non-mining states and the level of investment appears to have begun to stabilise in the mining states after substantial declines over recent years.

Business conditions are now around their highest level since 2008, and after some weakness in recent years, employment growth has been very strong this year.

Employment has increased by more than 371,000 persons over the year to September and 85 per cent of this was full time.

The annual growth in full time jobs is the strongest it has been in 6 years.

The strong employment growth may be encouraging more people to join the workforce, with the labour force participation rate now at its highest level since 2013.

Wages may have slowed in response to the period of slower growth and slack in the labour market in recent years but we expect that a period of stronger growth and falling unemployment will lift wages.

Looking abroad, the global economy has continued to improve as forecast at Budget, with further signs that global growth will strengthen. We have also seen growth that is more broad-based across advanced and emerging market economies.

Global factors are important for determining domestic economic outcomes.

Recent work by Treasury shows that, for a group of advanced economies, including Australia, more than 70 per cent of the variance in inflation is explained by a common global factor.

While this research shows that global drivers for GDP growth are more idiosyncratic, global factors are still important.

Recent meetings of international market regulators have highlighted that overall, some of the financial sectors risks in the global economy are improving.

And in its latest World Economic Outlook, the IMF raised its forecasts for global growth, to 3.6 per cent in 2017 and 3.7 per cent in 2018, a welcome upgrade after many years of downgrades to forecasts.

While some commentators were previously sceptical – and indeed at times we have received a lot of flak for our supposed exuberance – our Budget forecasts of a strengthening in Australian and global growth seem to be playing out.

This positive economic outlook also supports our fiscal position.

Government receipts are growing strongly at an average of 4.4 per cent per annum in real terms, while government spending is growing more slowly at average rate of 1.9 per cent per annum in real terms.

That restraint in government spending receives scant notice.

At the 2017-18 Budget, we projected that the Budget would return to an underlying cash surplus of $7.4 billion in 2020-21.

So while it is early days, at the moment the news is fairly positive.

Risks to the outlook

This doesn’t mean we can relax – these are still just forecasts and outcomes have mostly disappointed in recent years.

The housing market and household credit are areas we are monitoring closely.

In recent times, Australia experienced one of the largest booms in housing construction since Federation, supported by strong population growth and record low interest rates.

Currently, the household sector’s asset holdings are around five times greater than its debts.

That said, asset values can always fall (and often do) while debt values generally don’t, squeezing net worth in the process.

And we should not forget that around 75 per cent of household assets are in housing and superannuation – assets that cannot easily provide liquidity to households during periods of financial stress.

Australia’s financial regulators are alive to the risks presented by household debt, and will continue to closely monitor and ensure that we have a resilient financial system.

Of course, elevated levels of both household and public debt are a concern that is shared around the world.

High debt levels, whether private or public, make a country more sensitive to any changes in interest rates so this is not an issue that we can ignore.

This reinforces the importance of returning the Budget to balance, along with our ongoing regulatory work in the financial sector.

The risk of an economic shock emanating from China also remains, particularly given the levels of debt that have grown rapidly since the GFC

I visited China in July and was encouraged by my discussions with officials, who seem far more alive to the risks and, importantly, have room to manoeuvre.

This was also apparent at the recent 19th Party Congress.

The government’s strong control over the financial system, as well as the high domestic savings rate and level of foreign exchange reserves, will stand them in good stead.

It should also not be forgotten that their debt is overwhelmingly domestic.

Nonetheless, debt levels have been continuing to grow and the need to deleverage while maintaining acceptable levels of growth will be challenging.

It is also worth noting that after several years of unconventional monetary policy from key central banks, the US Federal Reserve is now starting to wind down quantitative easing.

It will now be interesting to see how this plays out as this wind down contrasts with ongoing quantitative easing in Japan and, to a lesser extent, in Europe.

Globally, tensions on the Korean peninsula continue to be a source of uncertainty from a geopolitical perspective.

However, it is important to remember that Australia has weathered significant shocks and volatility over the past decade fairly well, with our open and flexible economy standing us in good stead.

That flexibility is no accident – it is the result of a number of good policy decisions over several decades and that serves as a good reminder that constant vigilance is needed.

Conclusion

There really isn’t any single conclusion to draw from this address.

Put simply, as the mining investment boom ended, Australia has struggled with weak investment in the non-mining sectors, weighing on the labour market, productivity and ultimately economic growth.

Our ongoing work just reinforces the need for governments to pursue coordinated reforms that provide businesses with certainty, promote innovation and productivity improvements and support the ongoing transformation of the economy.

Thank you.